The mesh, the grid: the double

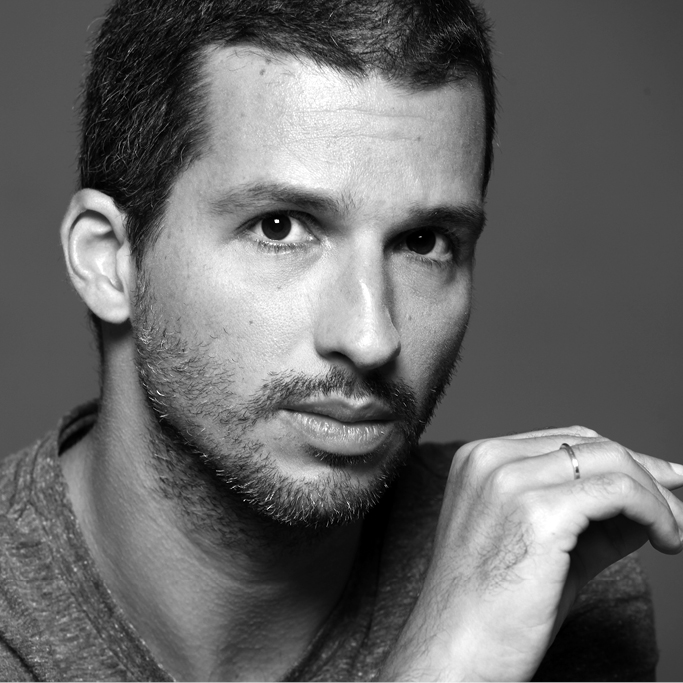

by Francisco Bosco

The engine that drives Raul Mourão’s oeuvre – beginning at a certain stage of formulation in which the obstinate character of questions denotes the consolidation of a gaze, a gesture, a singularity – is, in my understanding, a tension which could be described, within a chain of oppositions, as the one which exists between world and form, concrete and abstract, signified and signifier, heteronomy and autonomy. This tension generally starts out irreducible, non-synthesizable, under the guise of a double which establishes a presence/absence mechanism, and which the artist then unfolds into myriad possibilities, and tends to move towards the prevalence of the formal. At other times, as is the case with his widely known series on the former Brazilian president Lula (Luladepelúcia, Luladegeladeira, Luis Inácio Guevara da Silva), this tension resolves into works that synthesize signified and signifier, sense and sensible, social commentary executed as form and material. But generally, I repeat, there prevails a sort of tension, one that neither separates nor fuses its elements. In this show, MOTO (MOTION), this tension-engine is repositioned onto a set that sheds light on the general direction of his trajectory, consolidating it, enhancing it, and endowing it with new inflections. Let us review the “chapters” in the exhibit, so as to make these abstract observations more concrete.

One might say MOTO begins where everything begins to Raul Mourão: the street, experiences lived, the immediate. The first chapter is dedicated (also in the sense of a tribute, in memoriam) to the Chilean artist Selarón, found burned on the steps of the tiled Lapa staircase he designed himself. The set is titled Suicidaram Selarón (They’ve suicided Selarón). The ironic title is the Brazilian equivalent to Artaud’s original (Van Gogh, the man suicided by society): not so much the moral oppression as the cynical interplay between order and disorder (of which Lapa was the historical birthplace during the republican era of our history), involving the police, drug dealers, the press, government officials, in whose dirty game the artist was “suicided.” In media res, MOTO opens up by introducing a photograph depicting Selarón’s body being “mourned,” (photo: Bruno César/AFP) in a police cover-up (of which the covered body is a metaphor), under the inquiring eyes of a citizen, to whose left is a man in business attire (characterizing the porosity of the city’s social strata); farther to the left is a desolate man. The public work of art also mourns its author’s corpse, a metonymy for the murdering of art by political institutions.

Like a narrative, the chapter on Selarón is followed by chapter #setaderua (#streetsign), which resumes a series explored by Raul Mourão a few years back. While Suicidaram Selarón is consecrated to pure immediacy, to its shapeless violence (even though its double background is the work of art and its world of form), #setaderua introduces in a more explicit way the tension between immediacy and the medium, concrete and abstract, sense and the sensitive. Throughout the whole series, what we see is photographic compositions and paintings that concoct variations on that tension, as though the artist’s gaze never ceased to be amazed by the emergency and the perseverance of the formal in the face of its functionality. Thus being, the street signs are at once sense (function) and sensitive (form). They perform their tasks of detouring, circumscribing, orienting – and yet at the same time they transcend said utility, affirming themselves as form, graphism, composition, and cast their gaze upon the moments of greatest formal autonomy in the history of modern art.

This ambivalence between function and form is outlined more explicitly under the mechanism of the double, to which I have referred, in the chapter #agradeeoar (#thegridandtheair). Resuming his series on grids, the artist creates a two-way street, whose first three photographs exhibit grids within their social habitat, the world of objects, where their form disappears in their utility. In the sculptures, in turn, the process is reversed, and this time utility vanishes, suppressed by the environment, causing form to rise to the forefront. As in the Gestalt’s Rubin Vase, there is a play of presence and absence, of foreground and background: function is haunted by its double, which is form, and vice versa. There is an other in the image, indissociable but phantasmal, like the melody of a silent song that plays in our mind as we read a song’s lyrics; or, inversely, a lyric we read, deep down in our ears, as we hear the melody of a known tune whistled.

The next chapter develops and builds on this displacement of emphasis from the signified to the signifier, an operation which the critic Luisa Duarte has dubbed the “drying out”: a translation of experience driven by an “asepsis, a desiccation, a distancing of the subject from the living of experience.” The grid series – “geometry of fear,” as the critic Paulo Herkenhoff put it (and thus form and affection, stability and movement) – reconnects with its evolution in larger-scale structures that are openly autonomous, like those exhibited in Tração animal (Animal traction), at Rio’s MAM, 2012, which performed a “de-functionalizing of the functional,” as noted by critic and curator Luiz Camillo Osorio. Like an orchestral arrangement, these structures combined themselves with the street signs, duly “dried out,” and additionally comprise the element of lights and shade to give rise to the apex of this passage from the mesh to the grid, from real movement to abstract movement, a fundamental philosophical category. Not by chance, the artist calls this set of works Obra (Oeuvre). It also opens with street images (the photograph titled Little Richard, a tribute to the artists Richard Serra and Fernanda Gomes), which denotes the same tension between functional objects and their pure form, and then dries out experience through form. Thus, Obra is the chapter that brings the elements together and sheds light on the predominant direction to this trajectory; it is the process and its outcome; it is the construction material and the constructivism; it is, in the artist’s own words, “what connects different lived experiences, and turns them into artworks.”

Live presents one single recording, bearing down, as the title indicates, upon the fire of what has been lived, looking to capture it in the cold medium of photograph. Finally, Brog (Brog is the name of Raul Mourão’s blog) receives two images by other artists (Gustavo Prado and Joshua Callaghan), implying that the engine of the existential is also the others, and that an art piece cannot be created without the gazes of companions. After all, as one poet said – he himself inhabited by the tension between the primal character of rock and roll and the sophistication of concretism: “there is no sun in solitude.”